Week 3: The History of the Bedroom

As there are a multitude of different bedroom histories I have decided to focus on history of the English bedroom. The bedroom has developed greatly over the years, never changing in purpose but constantly changing as a social space.

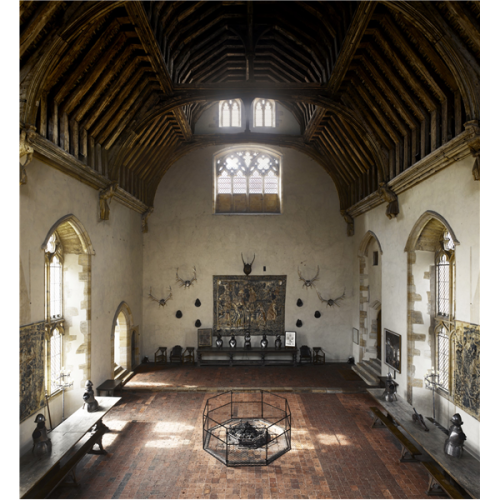

In medieval times the bedroom was a public and social space. The word ‘bedroom’ did not even exist. During these times all of the people who lived and worked on a property would sleep in the great hall owned by the Master of the property. This hall was a multipurpose space used for many different activities such as dining, working and sleeping. The idea of the bedroom developed during this time as the chamber. The Master and Mistress of the property would have a chamber room above the great hall. This chamber room was used as a sleeping quarters, but also used for dining and entertaining. It was not a private space, but a public space for select people, such as the Master and Mistresses’ family and close servants. This room was truly one of social hierarchy as it had a window that enabled the family to ‘look down’ on the plebeians.

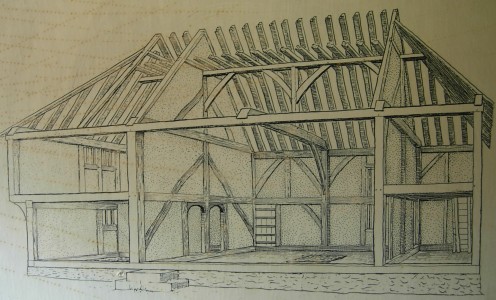

As we move to the Tudor era, a new class of people emerged. These people were called ‘middlings’ and were basically today’s equivalent of middle class. These people built their homes with bedchambers on the second level of the home. This room was a shared bedroom, and was still very much a public space. All people of the house, including servants, would sleep in these quarters, sometimes even on the same bed. This is also when the first proper beds started to emerge. Beds were often the most expensive item that a household owned, and were probably the most private part of the room, as the main bed would have curtains to provide little privacy for the couple of the household. If the couple wanted to engage in carnal relations, they would often have to wake in the middle of the night to have more privacy.

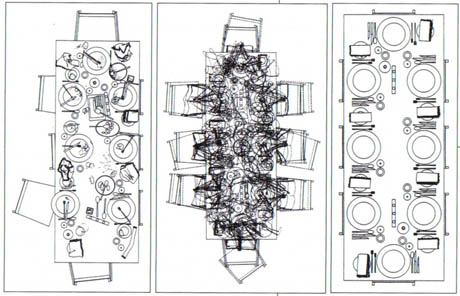

The 17th Century saw the bedroom become a larger space, yet still strangely public. In the Royal Family, the King and Queen would have their own private bedrooms, however, each morning both would be ceremoniously dressed in these rooms in front of an audience. The dressing ceremony was extremely hierarchical, with specific roles for each dresser. At the bottom of the dressing hierarchy was the ‘Page’ who would put on the Queen’s shoes. They would also entertain in their bedrooms, hosting small parties of people. The only time when their bedroom would be intimately private would be if the King were to visit the Queen’s room. This would never happen the other way around. Lower class people copied these practices by entertaining in their bedchambers and having public occasions such as marriages held in their bedrooms. The first truly private space emerged soon after, in the form of a closet. The Royal family and some wealthy aristocrats owned these. Closets were rooms off the public bedroom that were purely private and locked up by the owner. These closets were a manifestation of the owner’s personality and taste. For more common people, bedrooms were all linked to one another, and one would have to pass through one or two bedrooms to reach their own. In the Victorian era, however, the corridor was introduced to create privacy.

From the beginning of the bedroom until the Victorian era, the bedroom was a central place of the household and of the occupant’s lives. Often a person would be born in the bedroom, sleep in the bedroom, get married in the bedroom, give birth in the bedroom and die in the bedroom. However in the Victorian era, couples had their own bedroom, and bedrooms were seen as places that were strictly for sleeping (this rule did not apply to aristocratic or royal households). The industrial revolution allowed some people to indulge in the amount of rooms they created in their homes. For some wealthy industrialists, the couples had separate bedroom connected by a door. The husband’s room was referred to as the ‘dressing room’ and had another separate door that opened to the outside so that the husband could sneak back home after a night out and not disturb his sleeping wife. During the Victorian era, private bedrooms became more popular, however it wasnt until the Georgian era’s expanding economy that a private bedroom was a normality.

fig. 4: A bedroom of an aristocrat at Woburn Abbey used for entertaining. Typical of the Victorian Era.

In the 1930’s we see the emergence of the ‘boudoir’, brought on by the Hollywood culture and the emancipation of women. This turns the bedroom back into a space that is a slightly more public, multifunctional room. We see the desk returning to the bedroom and books being read in bed, which was probably done in the Victorian era, but widely frowned upon. It was during this time that people truly had their own private space, and were able to do whatever they pleased in their personal bedrooms. In the 1950’s the twin set beds became popular. They were a small step into the future, but paid homage to the Victorian predecessor of the luxury of having one’s own bed. It wasn’t until after the 50’s that it was common for couples to not only share a room, but to share a bed together as well.

Although the bedroom has not changed its fundamental purpose over the years, it has seen a great change in terms of its social purpose. From the extremely public bedroom of the medieval times, to the extremely private bedroom of the Victorian era, it has now found a happy medium between the two where it can exist as a private sanctuary for its owner, but also as a representation to the world of ones own personality.

References:

If Walls Could Talk: The History of the Home: The Bedroom, dir. Lucy Worsley (BBC, 2011)

Tyrrell-Lewis Associates, Social History, Bricks and Brass, 2001-2014 <http://www.bricksandbrass.co.uk/design_by_room/bedroom/bedroom_social_history.php>

James Duncan, Sleeping Around: A History of the Bedroom, James Duncan/Disciplined Eclecticism, 30 December 2010 <http://www.jamesstuartduncan.com/collections/2013/12/30/sleeping-around-a-history-of-the-bedroom>

Images:

fig. 1:

Alan Jacobs, Penshurst Place, The American Conservative, 8 January 2013 <http://www.theamericanconservative.com/jacobs/penshurst-place/>

fig. 2 & 3:

Mandy Barrow, Characteristics of Tudor Houses, Houses and Homes <http://resources.woodlands-junior.kent.sch.uk/homework/houses/tudors/characteristics.htm>

fig. 4:

Classic British Hotels, Woburn Abbey, 2013 <http://treasurehouses.classicbritishhotels.com/woburn-abbey/>

fig. 5:

Charles Vidor, Occurrence, Shadowplay, 23 August 2011 <https://dcairns.wordpress.com/tag/charles-vidor/>

fig. 6:

Luke Ferris, Top 5 Furniture in TV History, Worldstage, 30 April 2014 <http://blisstree-2012-stage.com/2014/04/top-5-furniture-in-tv-history/>